There are different kinds of smart. Especially when faced with a critical and timely decision.

One kind of smart would gather the immediately available data and make a decision within hours (possibly even minutes) and swiftly take the appropriate action. This solution may be about 80-85% correct.

Another sort of smart would painstakingly try to gather a perfect data set before making a decision. This may provide an answer that was 95-98% correct, but it would take weeks and the answer would come too late. The building would be burned to the ground. An opportunity would be missed. Productivity would be quashed. The benefits would not exceed the consequences.

The best decision one can make is the right decision. Share on X The second-best decision is the wrong one. The worst decision is not to make one at all. Or make one so far after the fact that the level of correctness becomes irrelevant.

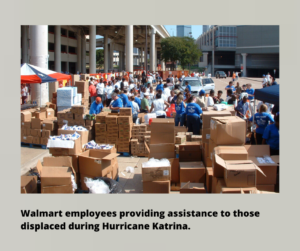

In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, as the level of devastation and chaos became apparent and as FEMA worked on an “ideal” method to requisition, deliver, and account for supplies, Wal-Mart decided to be a different kind of smart.

“A lot of you are going to have to make decisions above your level,” Wal-Mart CEO Lee Scott instructed his New Orleans-area team members. “Make the best decision that you can with the information that’s available to you at the time, and, above all, do the right thing.”

There was no other set of instructions.

Operating with the knowledge that speed is every bit as critical as accuracy during the triage portion of a crisis, Wal-Mart management and employees executed simple solutions that produced extraordinary results, including providing medications to hospitals that had run out, and providing food and water to the National Guard a day before FEMA showed up. The company’s effectiveness caused Jefferson Parish’s top official to remark to Meet The Press host Tim Russert, “If the American government had responded like Wal-Mart has responded, we wouldn’t be in this crisis.”

Operating with the knowledge that speed is every bit as critical as accuracy during the triage portion of a crisis, Wal-Mart management and employees executed simple solutions that produced extraordinary results, including providing medications to hospitals that had run out, and providing food and water to the National Guard a day before FEMA showed up. The company’s effectiveness caused Jefferson Parish’s top official to remark to Meet The Press host Tim Russert, “If the American government had responded like Wal-Mart has responded, we wouldn’t be in this crisis.”

The importance of efficiency in decision making applies beyond moments of crisis as well.

While looking back at key decisions made during his early days as CEO of Disney, Robert Iger reflected on his conclusion to dismantle Disney’s long-standing Strategy Planning department.

“They were often too deliberative, pouring every decision through their overly analytical sieve. Whatever we gained from having this group of talented people sifting through a deal to make sure it was to our advantage, we often lost in the time it took for us to act. This isn’t to say that research and deliberation aren’t important. You have to do the homework. You have to be prepared. You certainly can’t make a major acquisition without building the necessary models to help you determine whether a deal is the right one, but you also have to recognize that there is never 100 percent certainty. No matter how much data you’ve been given, it’s still, ultimately, a risk, and the decision to take that risk or not comes down to one person’s instinct.”

Knowing there is never 100 percent certainty means that sometimes a wrong decision will be made. While not ideal, even the wrong decision creates more positive forward momentum than no decision at all. Share on X

“Planning is great. Analysis is great. But most of the time when you get 80 percent of the facts, that’s really all you need to make a decision,” states Home Depot co-founder Arthur Blank. “To get to the last 20 percent could take forever. Make a decision and get on with it! We want our people to be unafraid of making mistakes. The only time people don’t make mistakes is when they’re asleep. And if you’re wrong, all we ask is that you be willing to step back, admit ‘That’s not working,’ and try path B or C.”

No person is perfect. No organization is perfect. And no decision is perfect either. As such, it’s pointless and often counter-productive to wait around for perfect data in order to make what will inherently be an imperfect decision.

Be smarter than that. Choose to be the best kind of smart.

# # #

SOURCES & FURTHER READING:

The Checklist Manifesto by Atul Gawande

The Ride of a Lifetime by Robert Iger

Built From Scratch by Bernie Marcus and Arthur Blank

Abstract thinking. Process of elimination Which brings thoughts to move on…and good ole gut feeling… When the obvious. just aint there .. and draw that line of do and dont… and dont forget about the weakest link

Great point, JP and something for me to cover in the future. Many times our decisions can be defined by either the weakest link or the biggest constraint.